Monday, February 13, 2006

Sunday, February 12, 2006

perFormaNCE aRt

Art History 101 - Performance Art

1960s to Present

The term "Performance Art" got its start in the 1960s in the United States. It was originally used to describe any live artistic event that included poets, musicians, film makers, etc. - in addition to visual artists. If you weren't around during the 1960s, you missed a vast array of "Happenings", "Events" and Fluxus "concerts", to name just a few of the descriptive words that were used.

It's worth noting that, even though we're referencing the 1960s here, there were earlier precedents for Performance Art. The live performances of the Dadaists, in particular, meshed poetry and the visual arts. The German Bauhaus, founded in 1919, included a theater workshop to explore relationships between space, sound and light. The Black Mountain College (founded [in the United States] by Bauhaus instructors exiled by the Nazi Party), continued incorporating theatrical studies with the visual arts - a good 20 years before the 1960s Happenings happened.

You may also have heard of "Beatniks" - stereotypically: cigarette-smoking, sunglasses and black-beret-wearing, poetry-spouting coffeehouse frequenters of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Though the term hadn't yet been coined, all of these were forerunners of Performance Art.

By 1970, Performance Art was a global term, and its definition a bit more specific. "Performance Art" meant that it was live, and it was art, not theater. Performance Art also meant that it was art that could not be bought, sold or traded as a commodity. Actually, the latter sentence is of major importance. Performance artists saw (and see) the movement as a means of taking their art directly to a public forum, thus completely eliminating the need for galleries, agents, brokers, tax accountants and any other aspect of capitalism. It's a sort of social commentary on the purity of art, you see.

In addition to visual artists, poets, musicians and film makers, Performance Art in the 1970s now encompassed dance (song and dance, yes, but don't forget it's not "theater"). Sometimes all of the above will be included in a performance "piece" (you just never know). Since Performance Art is live, no two performances are ever exactly the same.

The 1970s also saw the heyday of "Body Art" (an offshoot of Performance Art), which began in the 1960s. In Body Art, the artist's own flesh (or the flesh of others) is the canvas. Body Art can range from covering volunteers with blue paint and then having them writhe on a canvas, to self-mutilation in front of an audience. (Body Art is often disturbing, as you may well imagine.)

Additionally, the 1970s saw the rise of the autobiography being incorporated into a performance piece. This kind of story-telling is much more entertaining to most people than, say, seeing someone shot with a gun. (This actually happened, in a Body Art piece, in Venice, California, in 1971.) The autobiographical pieces are also a great platform for presenting one's views on social causes or issues.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, Performance Art has increasingly incorporated technological media into pieces - mainly because we have acquired exponential amounts of new technology. Recently, in fact, an 80's pop musician made the news for Performance Art pieces which use a Microsoft® PowerPoint presentation as the crux of the performance. Where Performance Art goes from here is only a matter of combining technology and imagination. In other words, there are no foreseeable boundaries for Performance Art.

What are the characteristics of Performance Art?

• Performance Art is live.

• Performance Art has no rules or guidelines. It is art because the artist says it is art. It is experimental.

• Performance Art is not for sale. It may, however, sell admission tickets and film rights.

• Performance Art may be comprised of painting or sculpture (or both), dialogue, poetry, music, dance, opera, film footage, turned on television sets, laser lights, live animals and fire. Or all of the above. There are as many variables as there are artists.

• Performance Art is a legitimate artistic movement. It has longevity (some performance artists, in fact, have rather large bodies of work) and is a degreed course of study in many post-secondary institutions.

• Dada, Futurism, the Bauhaus and the Black Mountain College all inspired and helped pave the way for Performance Art.

• Performance Art is closely related to Conceptual Art. Both Fluxus and Body Art are types of Performance Art.

• Performance Art may be entertaining, amusing, shocking or horrifying. No matter which adjective applies, it is meant to be memorable.

Source: Rosalee Goldberg: 'Performance Art: Developments from the 1960s', The Grove Dictionary of Art Online, (Oxford University Press, Accessed 01/17/04)

performance art, multimedia art form originating in the 1970s in which performance is the dominant mode of expression. Perfomance art may incorporate such elements as instrumental or electronic music, song, dance, television, film, sculpture, spoken dialogue, and storytelling. The roots of this art lie in early 20th-century modernist experiments with mixed media, particularly in Dada performances. The direct antecedent of performance art, however, can be found in the happenings of the late 1950s and the 1960s. Among the most obvious differences between the two is that the later movement tends to be much less spontaneous in nature than the earlier and that happenings were almost always created by visual artists, whereas performance artists generally have more varied backgrounds, many in theater, writing, or dance.

Primarily an avant-garde form, performance art is often emotional and topical, frequently dealing with political and personal matters and with issues such as race, class, and feminism. Probably the best-known contemporary American performance artist is Laurie Anderson; others include Nam June Paik (earlier also involved with happenings), Michael Smith, Vito Acconci, Carolee Schneeman, and Martha Wilson. Often classified as performance artists are such monologist-writers Eric Bogosian, Spalding Gray, Karen Finley, Anna Deavere Smith, and John Leguizamo.

Performance art is art where the actions of an individual or a group at a particular place and in a particular time, constitute the work. It can happen anywhere, at any time, or for any length of time. Performance art can be any situation that involves four basic elements: time, space, the performer's body and a relationship between performer and audience. It is opposed to painting or sculpture, for example, where an object constitutes the work.

Although performance art could be said to include relatively mainstream activities such as theater, dance, music, and circus-related things like fire breathing, juggling, and gymnastics, these are normally instead known as the performing arts. Performance art is a term usually reserved to refer to a kind of usually avant-garde or conceptual art which grew out of the visual arts.

Performance art, as the term is usually understood, began to be identified in the 1960s with the work of artists such as Vito Acconci, Hermann Nitsch, Joseph Beuys, and Allan Kaprow, who coined the term happenings. Western cultural theorists often trace performance art activity back to the beginning of the 20th century. Dada for example, provided a significant progenitor with the unconventional performances of poetry, often at the Cabaret Voltaire, by the likes of Richard Huelsenbeck and Tristan Tzara. However, there are accounts of Renaissance artists putting on public performances that could be said to be early ancestors to modern performance art. Some performance artists point to other traditions, ranging from tribal ritual to sporting events. Performance art activity is not confined to European art traditions; many notable practitioners can be found among Asian, Latin American, Third World and First Nations artists.

According to Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present by RoseLee Goldberg:

“Performance has been a way of appealing directly to a large public, as well as shocking audiences into reassessing their own notions of art and its relation to culture. Conversely, public interest in the medium, especially in the 1980s, stems from an apparent desire of that public to gain access to the art world, to be a spectator of its ritual and its distinct community, and to be surprised by the unexpected, always unorthodox presentations that the artists devise. The work may be presented solo or with a group, with lighting, music or visuals made by the performance artist him or herself, or in collaboration, and performed in places ranging from an art gallery or museum to an “alternative space”, a theatre, café, bar or street corner. Unlike theatre, the performer is the artist, seldom a character like an actor, and the content rarely follows a traditional plot or narrative. The performance might be a series of intimate gestures or large-scale visual theatre, lasting from a few minutes to many hours; it might be performed only once or repeated several times, with or without a prepared script, spontaneously improvised, or rehearsed over many months.”

Performance art genres include body art, fluxus, action poetry, and intermedia. Some artists, e.g. the Viennese Actionists and neo-Dadaists, prefer to use the terms live art, action art, intervention or manoeuvre to describe their activities.

A NIGHT OF LIVE ART AT PENGUIN CAFÉ WITH CHUMPON APISUK by Danny C. Sillada

gadget to another, he produces different sounds creating an ethereal and discordant noise, resonating with the recorded nocturnal sounds of the frog and cicadas at the background.

One riveting gesture is the swinging of a small microphone near the speaker, creating a rhythmic sound in a circular motion, as if time and space converge in a g-force to create poetry of sound and movement. On the other hand, there seemed to be an internal incubation of crossness that was released inside the artist’s chest in the process of swinging the microphone, more liberating than the title itself “Revenge”.

Ruiz’s penchant for electronic gadget explores the sound like a conductor of an orchestra with his own hands. But unlike an orchestra of musicians, Ruiz has the control of manipulating the sound to his own liking in a random and spontaneous manner. There is a certain degree of playfulness, though, in the process of his performance and his imagery evokes wonder and curiosity of a child.

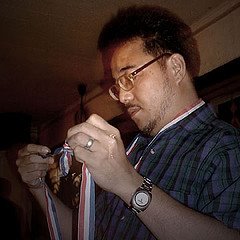

The third performance was done by this writer (Danny Sillada) titled “Sewing the Hole of Water”. With a bowl of water, I began to lay the white thread with silver strand through a large needle’s eye, and after pulling the thread in equal length, I knotted both ends. Then, I began to sew the imaginary hole, slowly with my eyes focused on the bowl of water; I dipped my right hand fingers with needle and thread into the bowl and pulled it up gently into the air as if I was sewing a sack of rice. A minute later, a red liquid leached into the air turning my fingers and the water into red, an image of blood appeared on the bowl.

‘Is there really a hole on the water?’ I asked the audience with rhetorical question. I explained that while there could be a space in-between the molecular structure of elements that composed the water (hydrogen and oxygen), ‘It is impossible to have a hole on the water…’ But that was beside the point. What I was trying to sew, if not to say, on the water was the rotten hole of our despicable economic and political conditions, the rotten hole of our constitution and the rotten hole of our political leaders.

The transformation of water into an image of blood on the bowl symbolizes the anguish and the predicament of Filipinos who could not see any faint light of hope from our tormented society.

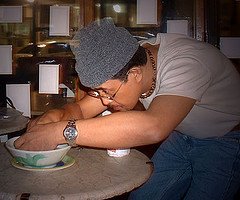

“Desserts/Stressed” was the fifth performance presented by Mitch Garcia. Sitting in front of the table with spoon and ice cream placed on the glass, she was relishing the sweetness on her palate. Every now and then, she would move her chair from corner to corner of the table as if she was trying to portray other imaginary persons eating with her. From time to time, she would wipe her mouth with unfolded tissue with an inscription of lipstick that said “Desserts/Stressed”. The two-word inscription was separated by a slash sign composed of the same letters but read differently with different meanings. When “Desserts” is read backwards, one can read “Stressed”.

Mitch Garcia’s performance is by no means an autobiographical feat about her diabetic condition. Suffering from diabetes in advantage stage, she struggles to balance her life and her career as an artist amid her pathological condition. When sugar diminishes in her body, she becomes weak and vulnerable to “stress” and to maintain the balance, she has to eat “sweet” food or inject insulin on her stomach to normalize the glucose level in her blood. Garcia’s performance brings her handicapped into a higher level of aesthetic pursuit and, as a performance artist, it becomes her own triumph.

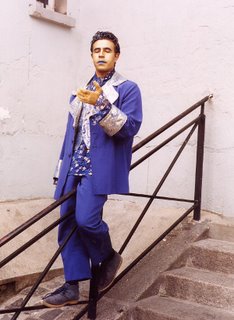

Jeho Betancor with his suave body movements, the seventh performance, examined the “self” on a mirror using objects as device of juxtaposing the inner persona titled “Mirror Image”. Betancor defined his space with a rectangular 35 X 60” white clothe; with apple on his mouth, he was embedding a 25 cent coins on the apple by hammering it with the mirror. Then, he took the apple from his mouth and soaked it with synthetic copper paint on a plate daubing his hands and arms in the process down to his stomach.

The reflection of shimmering paint on his arms and stomach with an apple portrayed a different visual image which seemed to mimic a metallic sculpture, thus making part of the artist’s body as a medium of both visual and performative acts. After that brief lingering act on his stomach, he put the apple on the floor and crushed it with his shoes. He then dropped on the floor pushing up and down as if he was finally releasing all the energy that runs through the creative process of his performance.

“Mirror Image”, although a complete performative act by itself, it also simulates the aesthetic process using the body movements, devices and visual imagery as a form to achieve the anatomy of art making.

The eight and the last performance was from the man himself Chumpon Apisuk with his piecehttp://ugnayan.motime.com/

One common element in presenting an imagery of reality is what Yuan Mor’O Ocampo called “the appropriation of form and content” in performance art. Like for instance, one of the powerful imageries of reality presented during the Ugnayan meeting at the Kanlungan Ng Sining last August 13, 2005 is a two-minute performance done by Bogie Tence Ruiz who appropriated his body as the direct form and framing device of his performance. Clad in a yellow long jacket, he confronted the audience by asking: “Do you want to see the real dick?”

The question immediately aroused or grabbed the imagination of the audience. He proceeded to unveil the ‘real dick’ by opening his yellow jacket. Instead of underwear, Ruiz wore a picture of Bush covering his private parts with a caption, “I am the real dick!” The audience laughed! As if it was not enough to satisfy the curiosity of the audience, Ruiz pulled out the picture of Bush while the audience anticipated whether he was going to reveal his private parts. But to everyone’s astonishment, it revealed other imagery – a caption that says “This ad space for rent”.

Ruiz’s unity of actions from the beginning of his performance created a series of symbols and then converged toward his last action to form a powerful imagery of reality using human body to attract attention working as advertisement. In similar manner, it can also become a powerful medium to inform, protest, advertise and even literally sell the flesh as commodity.

When a performer creates a framing device for a particular performance, the performer encapsulates the form and content within the created space and time to present the imagery of reality that addresses concrete realities, and in a way comprehensible, in presenting the truth through the eyes and mind of an audience. This revelation of realities is disclosed through the woven symbols of actions and devices which the performer uses to create imagery of reality.

the performance.

In the end, an effective imagery of reality entrances the audience and creates an awe-inspiring encounter in relation to one’s concrete realities and human experience. The aesthetic experience becomes a meaningful encounter and the encounter becomes an esteemed experience to reckon with for both the artist and the audience. On the other hand, the performer, this time, is finally liberated from the aleatory process of art making hidden from the depths of the artist’s soul and subconscious and thereby completing the revelation of truth.

Wrapped with masking tapes around his eyes, mouth, feet and fingers, Rommel Espinosa painstakingly untangled the masking tapes one by one, slowly and steadily until he is finally freed from all those entanglements. He stood up calmly and quietly and, in an almost inaudible voice, he uttered: “Ako nga pala si Rommel!” (By the way, I am Rommel).

© Danny C. Sillada

Posted by: dcsillada at August 16, 2005 07:55 link comments (3)

Saturday, 06 August 2005

UGNAYAN STATEMENT 2005

FPRIVATE "TYPE=PICT;ALT="

Wawi Navarroza: Live Performance & Poetry Reading at Danny Sillada One-Man Show, The Podium, July 4-10, 2005.

“Performance Art is an infinitely varying, enormously wide-ranging and yet an enigmatic activity. It may be read as an endless permutation of an individual action; a subtle equivalent of the spoken and written word. Performance Art is one of the most potent, intuitive and yet highly evolved strategy that can be used to comprehend the unknown. Performance Art is an expressed desire and a declared ACTION with a singular intent of heightening the consciousness of its audience."

"With our every action making, every artistic understanding must be subverted. With our very action making, conventional Aesthetics must be exploded.”

-Yuan Mor’O Ocampo, Artistic Director – UGNAYAN’05, the 4th PIPAF